On May 24, Atlantans will have the opportunity to vote on funding for three infrastructure packages totaling an estimated $750 million over the next five years. The first and second are sequels to the 2015 “Renew Atlanta” Bond, which funded a combination of transportation and other capital programs across the city. One would cover “vertical” infrastructure, primarily city facilities like recreation centers, police precincts, and fire stations, and the other would include “horizontal” infrastructure such as parks, trails, sidewalks, bridges, and complete street projects. The third ballot measure is a renewal of the transportation special purpose local option tax (TSPLOST) that Atlanta voters first authorized in 2016, and covers similar projects to those in the horizontal infrastructure bond. The city is referring to the combined package of ballot measures as its “Moving Atlanta Forward” program. The full project list is here.

These existing programs have been controversial due to poor transparency, redirection of funds to unpopular projects (e.g. this and this), and overpromising to the extent the city was ultimately forced to disclose funding shortfalls and re-baseline the programs. While existing funding will continue supporting projects for the next several years (only 61% has been spent as of February 2022), public perception of failure is already baked in. Transparency and reporting improved after the creation of the Atlanta Department of Transportation (ATLDOT) in 2019, but the city’s capacity to plan and deliver projects languished under poor leadership from successive mayoral administrations.

The city’s bureaucratic rot is deep, and while I’ve been encouraged by energetic leadership from new mayor Andre Dickens, turnaround of the magnitude necessary is more than a one-term job. City procurement and human resources have long been disasters, rendering the city incapable of properly staffing critical departments or executing projects on time and at reasonable cost. Atlanta was inadequately prepared to deliver the programs it put before voters in 2015-2016, and improvements since then have been marginal at best. There’s really no sugar-coating this.

And yet, these ballot measures present an opportunity to focus city leadership on crucial bureaucratic reforms, mold ATLDOT into a stronger and more capable agency, and capitalize on historic levels of federal support for urban transportation projects.

I’ll be voting yes on all three packages.

The arguments for “yes”

The case for these ballot measures is fairly straightforward. Atlanta has a backlog of critical maintenance obligations and a growing roster of high-priority, potentially transformative projects, and nowhere near enough funding available in the city’s general fund to pay for everything. While the city will need to implement aggressive reforms to deliver these projects on time and budget, underwhelming program delivery may be the costs of any future progress for Atlanta.

But we also now have a mayor with more energy and interest in effectively governing the city than any since Shirley Franklin, and an Atlanta City Council more focused on policy solutions and good governance than probably any ever. Mayor Dickens inherited a mess from his predecessors, but he deserves a chance (and the resources) to deliver the transformative change voters overwhelmingly endorsed in November 2021.

The previous TSPLOST and Renew Atlanta Bond programs were packed with too many projects and severely low-balled cost estimates. At minimum, the new project lists drafted for all three ballot initiatives are appropriately conservative with cost estimates and reasonable expectations of delivering all of them. City officials who drafted the plans even included a $31.5 million reserve fund to accommodate inflation. The wildcard is the extent to which inflationary pressures outpace that set-aside, and I suspect they will from my own recent experience working on transit projects.

But there are two ways in which the city can still deliver these projects under budget and possibly more than what’s on the official lists going before voters. We can improve project delivery along multiple axes that would reduce individual project costs (more on that in a bit), and we can seek out additional funding to supplement local dollars.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) makes billions of dollars in new funding available to cities, and these programs align remarkably well with the project list devised by city officials. And nearly all of these discretionary grant programs require local dollars to match federal funds. The city’s program webpage notes it will likely use some of these local dollars to match federal funding for bridge repair/replacement under the Bridge Investment Program.

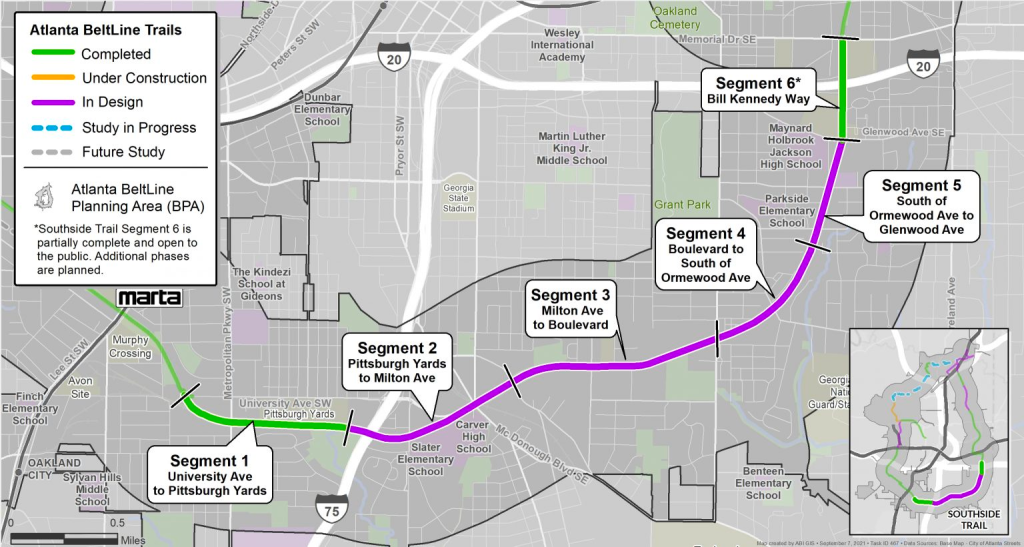

That’s just scratching the surface. The city can bring in tens of millions of dollars for sidewalks, trails, complete streets, and other active transportation improvements through a variety of other programs. These include the Safe Streets and Roads for All Grant Program, which will provide at least $5 billion over five years for planning and execution of capital projects, as well as a hefty set-aside for cities to develop or update comprehensive vision zero plans. Think $10-$15 million awards for the DeKalb and Cascade Ave Complete Streets projects, planning and/or capital awards for Proctor Creek and other PATH trails, or large programs combining multiple segments of sidewalks and bike lanes in a planned network.

The Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grants (formerly known as BUILD, and before that, TIGER) will offer somewhere between $1.5 billion and $3 billion each year through 2026, depending on annual appropriations, for a wide array of projects. In the past, these grants have contributed to BeltLine segments, streetscape improvements, and transit projects. The city can use any number of small dollar projects on its list as match for more transformative programs of corridor- or district-level improvements. The Biden Administration’s USDOT has made clear that it intends to snub road widening and highway capacity expansion projects, and focus on projects that promote transit and active transportation. On these huge discretionary programs and others, Atlanta should be in a good position to win large awards every year of the Biden Presidency, whether it’s the city itself, MARTA, PATH Foundation, or other local governmental entities.

We can choose to withhold additional funding for a couple years and hope the city demonstrates improved capacity to plan and deliver projects, but doing so would squander a historic opportunity to bring in federal funds to our city while watching them instead go to our competitors in Dallas, Charlotte, Nashville, and Miami.

Delivering more value for residents

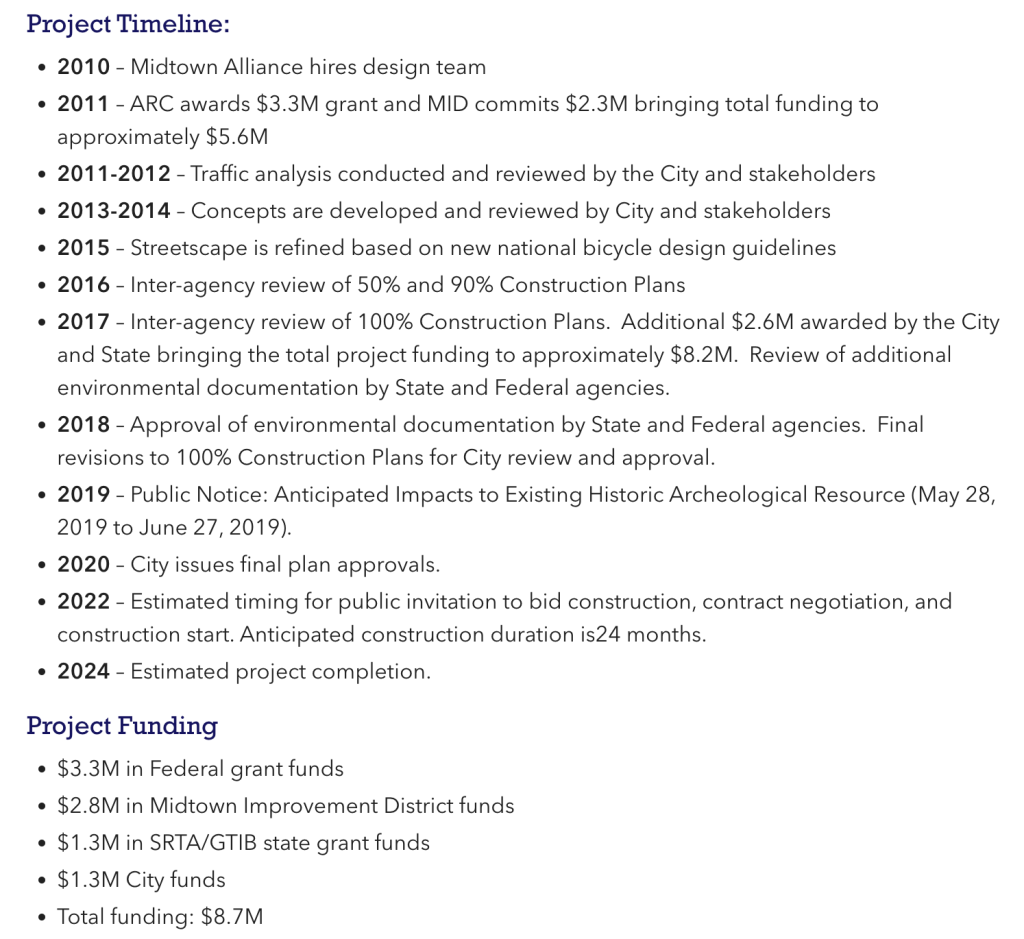

Atlanta’s struggles to deliver major projects is well documented, with perhaps none more egregious than the series of mishaps that put a single mile of Juniper Complete Street on a 15-year timeline. I won’t pretend to know every single driver of project complexity, cost escalations, and excruciatingly long schedules plaguing the city, but several are blindingly obvious. Antiquated and bloated procurement processes have never faced serious reform, and instead past mayors used a combination of forceful executive attention or unethical (or downright illegal) practices to bulldoze or circumvent red tape where needed.

I have seen multiple Atlanta transportation activists and elected officials argue for increased transparency and oversight of the Moving Atlanta Forward program should the ballot measures pass. Unfortunately, these actions would not address the root challenges inhibiting effective project delivery by the City of Atlanta. First of all, as I previously noted, transparency improved substantially following the creation of ATLDOT. Its online portal could use an improved user interface, and real-time funding tracking akin to what we see in the Commissioner’s quarterly updates to Council. I’d also like to see a master schedule of project phasing out to 2030 for this new batch of projects, and ATLDOT could throw in the legacy Renew/TSPLOST 1.0 projects for good measure. But the transparency is there.

Atlanta City Council should instead immediately turn to a more urgent priority that would pay far greater dividends. It needs to push an audit of city procurement and contracting practices, with an eye to significantly streamlining them over the next several years. Internal resistance from long-time employees and city lawyers will be fierce, but they’ve been lording over a badly broken process for too long and we need aggressive changes.

Moreover, the city has not committed appropriate financial resources to hiring strong transportation planners and engineers, and has been overly dependent on consultants to plan, design, and deliver projects. Outsourcing planning and design carries large premiums and risks of cost escalations from scope modifications and delays. Atlanta’s architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) consultancies are heavily oriented towards the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) and suburban municipalities because those have traditionally been more lucrative clients, and therefore our transportation talent pool is poorly-equipped for the types of active transportation (and transit) projects Atlantans increasingly demand.

That doesn’t mean these firms are incapable of delivering quality projects, but we’re certainly not in the position of Seattle, Boston, Los Angeles, Washington, or other US cities with more robust and innovative local transportation programs. Similarly, our local education pipeline (i.e. Georgia Tech) has a transportation engineering faculty mostly (though not entirely) oriented towards GDOT and its badly antiquated values, as that’s where the research dollars are. Those who are more oriented toward active transportation and transit often leave Atlanta for more innovative and dynamic cities, after feeling stifled by a sclerotic transportation culture. The upshot is we have a relatively thin local talent pool to deliver the sorts of projects on the program list.

We should be treating this large funding program as an opportunity for the City of Atlanta to hire more and better staff, which means raising salaries to competitive levels with the private sector. While this would incur upfront costs, it should also not only reduce overall project costs, but also reduce the amount of work and time required to bid out and contract with external consultants. We should also use the program to improve our local talent pipeline, deepening partnerships with Georgia Tech to train and recruit the next generation of transportation planners and engineers. (Most of this guidance similarly applies to MARTA and other local transportation agencies.)

While I have less visibility into construction costs, the city could take a similar approach there with more direct hiring of its project crews, and the sorts of technical college partnerships and apprenticeship programs described in Mayor Dickens’ Transition Report.

Finally, ATLDOT should use the program of projects to codify new standards for project design and delivery, and employ best practices from the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). Too many Atlanta transportation professionals have internalized the American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) “Green Book” of design standards, which prioritizes car and truck throughput over safety, urban quality of life, and accommodations for transit and active transportation modes. We’ve seen green shoots of a broader culture shift over the past few years, but ATLDOT has an opportunity to accelerate that shift both among its staff and the local consulting workforce by enforcing NACTO’s far preferable design standards.

The upshot

Healthy skepticism of Atlanta’s promises on transportation project delivery is warranted after years of disappointment, and I didn’t pull any punches in my assessment of the city’s failures or current capabilities. We need to have an honest conversation about the myriad factors contributing to our city’s (and region’s) culture of failure on transportation projects, no matter how uncomfortable, and how we can begin to fix it. However, the Moving Atlanta Forward package of infrastructure projects needs to pass on May 24.

I wrote in 2019 and again in 2020 that Gwinnett should vote yes on its transit referenda. Its failure to pass either initiative, the second by a mere 1000 votes, will cost the county hundreds of millions of dollars in federal transit funding to support local projects over the next five years. US transportation policy is arcane, and we can hardly expect rank-and-file voters to fully understand how project funding works. But we do need to remind them where possible that more money is at stake than solely the number advertised in these “pro-” campaigns.

Atlanta’s $750 million investment would allow it to bring in significant federal funds and maximize the local impact of its program. It also provides an opportunity to boost staffing and reform city operations. Ideally, ATLDOT uses these projects to develop stronger in-house capabilities, which would pay dividends beyond those five years of revenues. It can create a well-oiled machine that continues to deliver new sidewalks, bike lanes, trails, and other public works projects.

Mayor Dickens, ATLDOT, and this City Council all deserve a fresh chance to deliver a program of projects that would finally begin to transform Atlanta in ways that make it safer, more sustainable, and more livable. I encourage my fellow Atlanta voters to give them that chance.

you hit the nail on it’s head on transportation engineering and planning talent being severely underpaid and fleeing Atlanta. As a GT transportation engineering alumni, almost everyone in my cohort left Atlanta. Not enough complete streets and transit work to keep us all employed fruitfully at a competitive salary. Just a few years ago, it was either a 45k salary at GDOT, or 60-70k in the West Coast for new graduates. And all of the west coast cities have plentiful progressive projects to work on.

LikeLike