In Part 1, I introduced my recent decision to buy an electric vehicle (EV), and how market changes over the past few years resolved my indecision. This second entry in the series covers technology and infrastructure considerations influencing my decision.

I recently saw this graphic posted on Bluesky contrasting the 2011 Nissan Leaf to the 2025 Chevy Equinox EV. It highlights tremendous improvements in EV technology since the Leaf debuted as the world’s first mass market model…in powertrains, lithium-ion batteries, and power electronics to support vehicle charging.

The graphic actually understates engineering and manufacturing improvements we’ve seen since the first Leaf, as it fails to adjust retail price for inflation. The 2011 Chevy Volt plug-in hybrid (PHEV) launched with 35 miles of all-electric range and an even pricier $41,000 sticker on its base model.

The decline of sedans in favor of large SUVs and pickup trucks has also pushed the nominal average price of a new vehicle to more than $48,000 at the end of 2024. While most 2025 Equinox EV buyers are unlikely to find a $35,000 base model, it’s emblematic of what the industry has achieved to simultaneously reduce technology frictions for prospective buyers and position vehicle pricing for increased affordability.

Unless you’re into drive style and performance, there are really two EV technology areas that matter: 1) batteries and 2) charging capabilities. The former (plus drive efficiency) will dictate range, and the latter maximum charging speed and compatibility with different charging networks. Here’s how I’ve evaluated both.

Batteries

That 2011 Nissan Leaf came equipped with a 24 kWh battery pack, limited by the then-$900+ per kWh hour cost of lithium-ion batteries. The 73-mile range was fine for a city car, but not suited to most commuters.

Buoyed by rapidly falling battery costs, OEMs have been able to increase pack sizes in their vehicles to meet a broader swath of the consumer market. The 2025 Chevy Equinox delivers more than 300 miles of range with 85 kWh of battery.* Batteries north of 70 kWh have become the norm, with only a handful of OEMs offering smaller packs to achieve lower retail pricing.

*Technically the battery pack is larger than 85 kWh, which is the usable capacity. OEMs advertise the usable figure, not the actual size.

Today, mid-market BEVs tend to fall into one of three groups on range:

- 100-150 miles – Mostly legacy compact cars like the Leaf. They’re city cars primarily for households with other vehicles that can meet longer distance needs.

- 220-280 miles – Lower-cost versions of models with longer-range alternatives. These market affordability, and still primarily cater to multi-car households.

- 300+ miles – Most OEMs have converged on 300 miles as the magic number for mass-market consumer acceptance, and have sized their batteries accordingly.

As a driver though, the nameplate battery capacity is less meaningful than what you actually expect get out of it. Specifically range and charge time (a product of capacity and charge speed). If you’re like me, you routinely run your gas tank down to a couple gallons trying to minimize service station trips, knowing every gallon of refueling will cost you mere seconds versus an extra stop.

It’s unadvised behavior in a gas car, but even more so in a BEV. One should expect to use only 70% of their battery on a routine basis to preserve battery life, meaning that 319 miles of Equinox nameplate capacity really translates to ~225 miles in range. Fully charged for a roadtrip, you can use maybe another 20% of the capacity to get above 270 miles. And that’s before factoring in other performance variables.

So for any road trips that feel borderline on mileage, such as the 250 miles from Atlanta to Nashville or Savannah, I’d likely need to plan for a charging session.

Battery performance

While much of the concern over EVs and cold weather viability is overstated (heck, look at Norway) EV buyers living in colder climates will need to anticipate reduced range as a regular feature. Especially in places where the temperature routinely drops below freezing. Though performance starts to decrease below ~50°F, the effect is pronounced below ~40°F.

Fortunately, sustained temperatures at or near freezing are uncommon in Georgia, and therefore I don’t really need to factor them into my purchase decision. Temperature may affect winter road trips longer than 4-5 hours, but these will be rare and I can mitigate the problem with garage preconditioning and/or additional mid-trip charging.

If you frequently haul heavy payloads or tow, you can also expect range impacts. I don’t, so…I don’t.

The final battery consideration is lifecycle and replacement, for which the conventional wisdom has shifted recently. We’re starting to see that batteries are lasting longer than previously expected, potentially extending beyond 10 years and even matching vehicle lifespans depending on usage. As we see lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery chemistries integrated into US vehicles, those batteries will last even longer.

Degradation is still a concern, though. 319 miles of maximum range at purchase may be closer to 300 after tallying 50,000 miles. My own preference for a new vehicle with a battery sized for 300+ miles stems from not wanting to worry about degradation’s effects on my road trips, or any other range variables. Given my low annual mileage, I expect the battery will hold up through my ownership the vehicle if I choose to finance. Leasing would eliminate those concerns altogether.

Charging

Like most prospective EV drivers, I care about infrastructure availability at home and on major highway corridors, access to the Tesla Supercharger network, and maximum charge rates.

Charger availability

My condo building participated in a Georgia Power make-ready program that subsidized charger installations in our garage, and at the time of application we needed to offer up residents willing to buy chargers. As a good EV advocate who felt he’d be purchasing an EV soon, I signed up and bought my very own Level 1 charger, which was installed in my parking space. That was November 2021; it’s been collecting dust ever since.

But that means I’m still in the position of having access to trickle charging in my parking space. Yes, it’s pathetically slow, but more than enough to meet my needs to avoid public Level 2 charging. And probably just about anyone else who’d buy a condo in Midtown Atlanta. It’s good enough for at least 50 miles of recharge overnight. Even returning home from a roadtrip with a low state of charge (SOC), I’d replenish my battery over the next several days. If l sell my place and buy a townhome or house, I can buy a Level 2 garage unit for home charging. Georgia Power offers a rebate for that too.

Georgia now has more than 2100 public charging stations and 5600 ports throughout the state, with DC fast chargers comprising roughly one-fifth of those. That buildout is concentrated heavily around metro Atlanta, but the network along our major highways is also starting to come together. The Interstate corridors connecting Atlanta with Charlotte (I-85), Nashville (I-75, I-24), Savannah (I-16), Birmingham (I-20), and Charleston (I-20, I-26) have at least one Tesla Supercharger along them, as well as a growing footprint from Electrify America, ChargePoint, EVgo, and others.

The network as it exists increasingly looks good with access to the Tesla network, and doable with charger availability and reliability steadily improving across other networks. Having access to the Supercharger network would put to rest most concerns about charging access.

Supercharger access

After Ford CEO Jim Farley announced in summer 2023 his company would adopt Tesla’s “North American Charging Standard” (NACS), and struck an agreement with Tesla for access to its charging network, every major OEM scrambled to make their own deals. With Tesla’s much-larger footprint of reliable DC fast chargers across the country, access to its network has become an effective necessity for other OEMs as they market their vehicles to consumers.

As of this writing, Ford, GM, Rivian, Volvo, Nissan, and Polestar already have access to Superchargers. Hyundai and Kia are imminent. By the end of 2025, it’s likely every OEM will have network access, so few buyers should feel deterred on that measure.

I’m also evaluating when non-Tesla models will feature NACS ports built into the vehicle. The 2025 Hyundai IONIQ 5 will be the first “NACS native” model, with other automakers following suit in 2025 and 2026. Some OEMs are offering NACS adapters (free or otherwise) until they can introduce their NACS native models. But adapters are less preferable than installed charge ports, and may be subject to other hardware issues.

I expect some prospective buyers will want to wait for NACS native models, but I probably won’t. I’m slightly concerned about residual values for non-NACS vehicles, but leasing would address that.

Charge speed

In my simpleton’s terms*, most EVs manufactured today still feature a 400V architecture, which limits the electricity currents they can support. Even as charging networks roll out ultrafast chargers (350+ kW), most EVs on the market today won’t ever be able to accept those charge speeds. They’ll top out at 150 kW, which is good enough for the popularly-discussed “30-minute highway charge.” Multiple luxury models offer 800V architectures, but thus far only Hyundai and Kia feature it in market mid-range vehicles.

* I last formally studied physics in high school, and wasn’t very good at it, so I’ll leave the detailed explanation and math to others (i.e., just Google it).

As with NACS charging, this is an technology area where the industry consensus is set and we’re just waiting for OEMs to engineer and build the next-generation feature into their new models. The primary upshot of 800V architectures are charge rates above 200 kW and charge times as low as 10-15 minutes. It’s another reason I might consider a lease if I ultimately choose a vehicle model with the more basic 400V architecture.

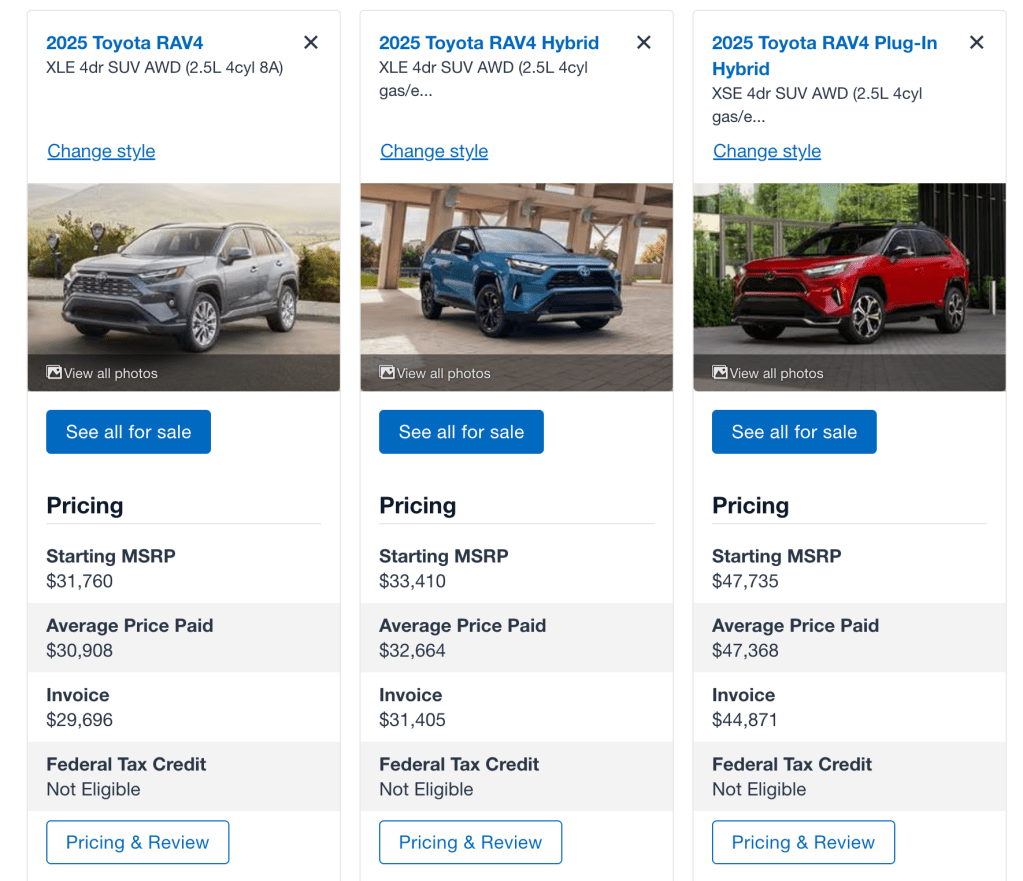

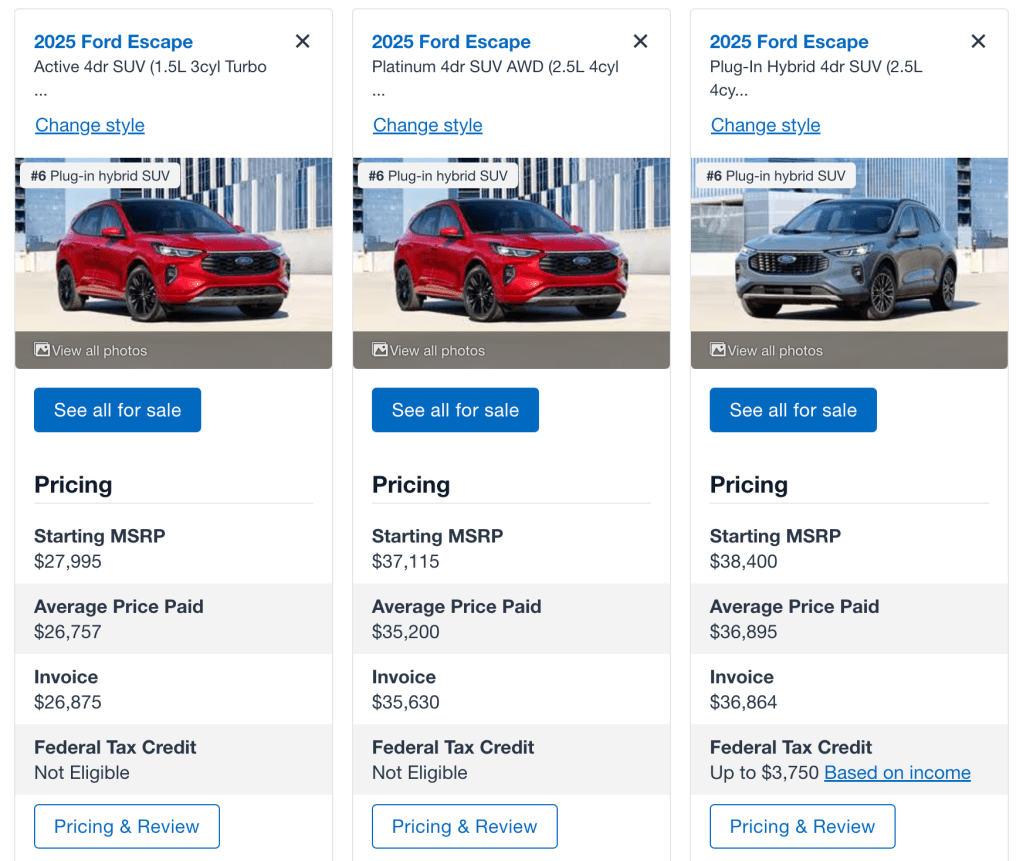

Plug in-hybrids

And now for an obligatory discussion of PHEVs…

I noted in my Part 1 post that automakers largely abandoned PHEVs several years ago, misreading Tesla’s success as an indication there was no longer-term market for this “transition technology.” That only finally changed in 2023-2024, with OEMs such as GM, Ford, and Hyundai recognizing the need to reinvest in PHEVs for a longer-than-anticipated transition. We’re still a couple years from seeing the fruits of that heel turn.

The lack of recent investment has left the PHEV market littered with modified ICE models packing in small batteries and parallel electric powertrain to a gas tank and engine. The batteries have steadily grown larger in capacity over the past few years, with most now around 14 kWh and offering 30-40 miles of all-electric range before the gas engine kicks in.

Consumers effectively pay for two powertrains in a body designed for gas combustion, which means losing the style and performance benefits of fully-electric architectures, while paying more than ICE and conventional hybrid (HEV) variants. This can increase the base vehicle cost by $10,000-$15,000 over those alternatives. Moreover, few OEMs have prioritized 30D tax credit qualification in production planning for their PHEV models, leaving few models eligible.

The result is a rather unappealing landscape.

I’ll cover incentives and overall value in Part 3, but I found PHEVs usually make sense only if you’re committed to going electric, but still can’t get comfortable with a BEV due to range and/or charging infrastructure. Alternatively, brand-loyal luxury car-buyers may find their preferred OEM still doesn’t make an appealing BEV, and opt for the PHEV variant of a popular gas model. In either case, you’ll be buying the PHEV more for environmental reasons than economic ones.

Other technology considerations

There are a few technology areas other buyers may care about, but won’t factor into my decision. For starters, I don’t care about vehicle speed or power.

There’s also been a impassioned debate over the past couple years about the march toward “software-defined vehicles” built around touchscreens and voice controls, at the expense of buttons. I like being able to adjust volume or temperature without looking at the control panel, but that’s not enough to meaningfully influence my decision.

Finally, driver assistance features are a low priority. My 4Runner is of an age where backup cameras and infotainment systems were standard features, but other safety and convenience technologies were not. So while I’ve had experience with blind spot assistance and lane departure warnings in rental vehicles, and limited experience with adaptive cruise control and lane-keep assist, I haven’t treated the current generation of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) as priorities. Nor am I willing to pay more for Tesla Autopilot, GM SuperCruise, or comparable automated driving packages.

The software technology is changing so rapidly that any vehicle purchased today will feel outdated in several years. So my philosophy is to accept that what I buy will be an improvement over my current ride, and leave it at that. Fundamentally, this is my first EV purchase, and my primary technology concerns are utilitarian. Can I drive where I want, charge as little away from home as possible, and access highway charging when needed?

The rest I can hash out at the dealership.

3 thoughts on “I finally decided to buy an electric car. Here’s what it means for EVs in America (Part 2)”